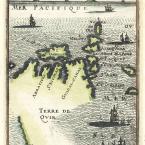

Isles de Salomon

Vanuatu is a country which lies in the tropics and has an average 75 inhabited islands. It's made up of volcanic islands with uplifted limestone terraces. We have over 130 languages in a population of about 250,000 people, and which makes us one of the most culturally diverse groups of people on this planet.

When de Queirós first came in 1606, he was trying to find this great southern continent in the name of King of Spain, but also in the name of Christendom, and Christianise the islands on behalf of the Pope and this depiction of the map greatly depicts this notion of this great lost southern continent. It shows currently today three or four different nations all combined together in this one particular map, Terre de Queirós in the middle, probably in representation of current Vanuatu. De Queirós most probably did not circumnavigate these islands thoroughly.

De Queirós was going to set up a town, but one of his biggest mistakes was – one of the first days he was there, one of his crew members killed this local, cut him into pieces and hanged the body up on a tree. And on top of it, his crew and his entourage were carrying out raids in the villages, stealing food. And so, there was a bit of skirmishes for some time, fighting going back and forth. Eventually, after some time, de Queirós realised that his town was not going to be successful, and his crew were getting sick, and so he had to abandon the idea, the notion, of building a town.

In 2006, the government at that time did a very big celebration for the 400-year anniversary of de Queirós in Vanuatu. It was all showing the good sides of the visit. At that time, they were celebrating the coming to ‘civilisation’ of Vanuatu, shall we say, and so it was much celebratory event, not so much a sober remembering the hardships event. People today see de Queirós with – I would not say happiness.

Quiros’s quest

In Vanuatu, the oldest evidence of human habitation is 3,050 years old. When our early ancestors left Papua New Guinea about 3,500 years ago, they followed each island as they saw it, because in Papua New Guinea, you can see the islands in the Solomons and from the southern islands in the Solomons, you can see islands in Vanuatu.

So initial migration into Pacific was from island to island as a stepping stone method. So about a thousand years before today, the whole of the Pacific was settled. Migration wise, there's been a lot of evidence to show that during this initial period of colonisation of the Pacific, people were constantly on the move, coming and going. We have identified artefacts which were made in New Caledonia, for instance. There's pottery made from northern parts of Vanuatu, whether Malekula or southern Solomons which shows that people were moving and trading with these artefacts. Some things and items that can produced in one island, most probably cannot be produced in others, and some tools for instance.

So people would travel and trade for that not only island to island or across nation borders, but also from coast to the interiors of each island, where all that trading went – well, was going on. Not only that, we have identified signs of people actually moving. When you are born in a certain area, the food which is derived from the land in that area, the chemicals in that particular food, that leaves a little pattern, stamp mark shall we say, in your skeletal remains, which can be used later on to identify your place of birth.

And so, we have identified certain elders which were not born on Efate, on the island which they're buried. They were born somewhere else, but this shows that they migrated. So especially with the initial settlers, we have identified signs of migration; not just one-offs, but people coming back and forth continuously. This can be attributed to the trade networks which they have, had at that time, moving on to settle other places, but keeping into contact with those people you've moved out from. This has continued up until European arrival.

When they started demarcating nation borders, they started preventing people from travelling to the next place. For example, our grandfathers could not travel to New Caledonia because you had to have a passport, and that blocked these routes, these trade routes which our ancestors had in their past.

Archaeological evidence

The Pacific Ocean, to a lot of people, might be seen as a barrier. Our ancestors saw the ocean as a way, as a road to get somewhere. They discovered new methods of navigating this Pacific Highway. Firstly, the invention of the double-hulled canoe, commonly today known as the catamaran, was invented by the Lapita people when they initially came to the Pacific, and with that technology, they managed to settle all the islands in the Pacific within a span of 2,000 years, from Papua New Guinea to the middle of the Pacific, Tonga, Samoa, right up to Hawaii, Easter Island and New Zealand.

The double-hulled canoe is built in a way that it can navigate through very rough waters because it balances itself out. But also, the Pacific would not be able to be settled without the knowledge and wisdom the people brought with them. They came up with – obstacles they came up, they found different solutions. With navigation, it is quite well known, our ancestors who navigated the Pacific did not have maps, but they did have – use the stars. Parts of Vanuatu, you'll go and there'll be some elders who still have some knowledge of the stars and how to navigate using the stars. And that, I think, was the most useful skill for navigation which they had.

And with this knowledge, people – and I've heard lots of lots of oral tradition, not only in Vanuatu but other countries I've been to, where people were just travelling like mad, back and forth. You'd have huge war parties from places like Tonga and Samoa, going everywhere.

Pacific highway

A lot of useful information that our ancestors had lived with that has sustained them for thousands for years on our islands are lost. With the rigorous approaches of missionaries condemning the local cultures and heritage, a lot of people on the islands have lost important aspects of their cultural heritage, of their traditional knowledge. We know not all of it's lost and we know it can still be revived. The biggest issue we're facing, because we've had over a hundred years of European colonisation, people's mindsets have changed. A lot of people in Vanuatu today, and in the Pacific as a whole, have come to rely on what is coming from outside as being best for us to live in.

If I want my life to be better, I have to look outside. Of course we know the technology we are currently getting from outside can make life easier. But the question is can it make it better and we are facing a very big battle at the moment trying to revive some of these useful traditions, and the biggest obstacle we face is decolonising people's mindsets. As a country that we are trying to develop in a sustainable way, it is best to look within ourselves and within our strengths, within the knowledge that we have, to put that in as a foundation for us to step on to develop. We just have to believe in it.

Looking within